Briefing: how the British Museum’s Arctic exhibition is at odds with its partnerships with major polluters

What happens in the Arctic happens to the world.

At this very moment, Indigenous communities in Alaska are resisting a push by the Trump administration to allow oil drilling in one of their most sacred places. We are taking action in solidarity with them, and with groups across Alaska and the US, to protect the Arctic and stop oil extraction in sacred lands.

At the same time, the British Museum is putting on an exhibition, ‘Arctic: climate and culture’, that shines a light on the challenges faced by Arctic Indigenous peoples today.

Yet the museum hypocritically continues to partner with fossil fuel companies and their financial backers:

- Its partner of 24 years, BP, was the biggest operator in the Alaskan Arctic for 60 years, producing over 13 billion barrels of oil

- The sponsor of the Arctic exhibition, US bank Citi, is the world’s third biggest funder of fossil fuels and backer of many pipeline and drilling projects actively opposed by Indigenous communities

The museum cannot have it both ways. If it wants to sound the alarm on climate change it must be honest about its causes – fossil fuel emissions and continued oil drilling by firms like BP. These partnerships with BP and Citi clash with the important message and purpose of the exhibition and the struggles against fossil fuel exploitation and climate change facing Indigenous peoples across the Arctic today.

We stand with the Gwich’in and Inupiaq peoples to say:

‘Sacred lands are not for sale. Stop Arctic oil extraction!’

For more information on the day of action, visit Native Movement, Defend the Sacred Ak and Sovereign Iñupiat for a Living Arctic (SILA).

Siqiñiq Maupin, Community Organizer for Native Movement and Sovereign Iñupiat for a Living Arctic (SILA):

“The attack on Alaska as a whole has been overwhelming. Our food, water, and air has been contaminated to the point of serious health impacts to humans and our relatives on the land and in the sea, We are seeing warming of the land that sustains all life at two times the rate of the rest of the world, endangering basic needs as the climate crisis worsens. In the midst of a pandemic that disproportionately affects BIPOC communities, we must take a stance against any further fossil fuel extraction and continued harm against our People. We are experiencing a shift in global consciousness from a system rooted in white supremacy into systems rooted in Indigenous ways and values. We must transition into an equitable and sustainable future for all beings.”

Full briefing:

- The British Museum’s Arctic exhibition

- The Arctic is under urgent threat from oil development

- BP’s history of Arctic exploitation

- Citi: funding climate change and trampling Indigenous rights

- FAQs

-

The British Museum’s Arctic exhibition

The British Museum’s new exhibition ‘Arctic: culture and climate’ (22 Oct 2020 – 21 Feb 2021) focuses on:

‘how Arctic Peoples have adapted to climate variability in the past and [are meeting] the challenges of global climate change today. Through the knowledge and stories of Indigenous Arctic Peoples, the exhibition addresses the global issue of changing climates in a transforming world.’

It has been developed in collaboration with Indigenous Arctic peoples and is perhaps the first time the museum has talked so explicitly about climate change, having come under intense pressure in recent years over its long-running partnership with fossil fuel giant BP.

It has been developed in collaboration with Indigenous Arctic peoples and is perhaps the first time the museum has talked so explicitly about climate change, having come under intense pressure in recent years over its long-running partnership with fossil fuel giant BP.

The museum’s decision to put Indigenous voices, perspectives, experiences and art front and centre in this exhibition is to be welcomed but we are concerned that its powerful message about climate change is clearly in conflict with the museum’s high-profile partnerships with BP and Citi. Both have played a significant role in driving dangerous climate change as well as opening the Arctic up to oil and gas drilling in the past.

What happens in the Arctic happens to the world. At this very moment, Indigenous communities in Alaska are pushing back against an imminent threat from the Trump administration to allow drilling in one of their most sacred places. Yet the museum continues to partner with and promote fossil fuel companies and their financial backers.

The museum cannot have it both ways. If it wants to sound the alarm on climate change it must be honest about the drivers of that climate change – fossil fuel emissions and the determination by oil giants like BP to keep drilling beyond 2050. These partnerships with BP and Citi clash with the important message of the exhibition. The stories, culture and traditions of Indigenous peoples should be presented without ethical conflict.

There is no place for oil companies in our museums during a climate crisis. The British Museum must do better.

2. The Arctic is under urgent threat from oil development

Right now, Arctic peoples are facing the double threat of climate change and increased fossil fuel extraction. We are expressing our solidarity with Indigenous organisations in Alaska, including Native Movement, Defend the Sacred Ak and Sovereign Iñupiat for a Living Arctic (SILA), to help sound the alarm on proposed drilling in their sacred lands.

‘The Sacred Place Where Life Begins’, which in the Gwich’in language is ‘Iizhik Gwats’an Gwandaii Goodlit’, is otherwise known as the coastal plain of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. It has been under threat from oil and gas exploration since 1987.

Located in North East Alaska along the Beaufort Sea, the Refuge is sacred to Indigenous people and home to numerous species of animals, who have migrated and lived in relation to that part of the earth for over 10,000 years. It is the birthing grounds for the Porcupine Caribou Herd, one of the largest migratory caribou herds in North America. The herd has the longest land migration of any animal in the world, but is under extreme pressure from the fast-changing climate.

The Porcupine Caribou Herd knows no borders, akin to their relatives the Gwich’in and Inupiaq, whose Peoples have lived in relationship with them across what is today known as Canada and Alaska’s Arctic. Indigenous Peoples are the original keepers of the ecosystem, which they believe needs to remain protected from industry and climate change. They continue to protect the land, and their way of life, into the future.

After Donald Trump’s election in 2016, a fast-track bill to throw out protections for the Sacred Place Where Life Begins was passed in December 2017, which included a provision mandating leasing and development for oil exploration. The administration has repeatedly demonstrated its willingness to pursue “energy dominance” over democratic process, exploitation over honoring the sacred relationship between people and the land, and a willingness to contribute to global greenhouse emissions while exploiting Indigenous peoples and stripping them of their lives and relationship to their environment.

Today, the Trump administration is poised to open up the refuge to bids for leases from oil companies, threatening ecosystems that are crucial for local food security as well as the health of our planet.

This could be announced any day.

So we are joining with groups across Alaska and the US to say ‘Sacred lands are not for sale. Stop Arctic oil extraction!’

3. BP’s history of Arctic exploitation

The British Museum has a long-running partnership with BP which, as well as being one of the world’s biggest polluters and drivers of climate change, has also been the biggest operator in the Alaskan Arctic for 60 years. Over that time, it has produced over 13 billion barrels of oil from its Prudhoe Bay operation, the US’s biggest and most productive oil field.

BP has been responsible for several oil spills in the Alaskan Arctic due to its negligence, as well as air pollution impacting the Indigenous communities living nearby. Massive amounts of carbon emissions from its global operations have also helped to fuel the devastating climate change now being witnessed in the Arctic.

BP has long been one of the companies angling to drill in the Refuge, and holds a lease for exploration there which it renewed last year. It actively lobbied the Trump administration to relax regulations so that it could undertake both high-risk offshore drilling in Arctic waters and in the Refuge. That self-interested lobbying proved successful, as we are now seeing. Last year, Gwich’in and Inupiaq people made their views clear at BP’s AGM, strongly urging the company not to pursue drilling in the Refuge.

Perhaps partly in reaction to this pressure, as well as the multiple challenges now facing major oil companies, BP recently took the decision to sell its entire Alaskan operations to another company, Hilcorp, including the lease to drill in the Refuge. This doesn’t mean that BP is now free from its responsibilities for its impacts in the Arctic or no longer accountable for whatever happens next. If BP was serious about wanting to tackle climate change, it would be winding down its operations in Alaska, leaving the remaining oil in the ground and making sure that the lease is never acted upon. Instead, it has guaranteed that every last drop in Prudhoe Bay will be extracted – there are estimated to be another billion barrels there – and that the Refuge will continue to be a target for oil exploration.

Perhaps partly in reaction to this pressure, as well as the multiple challenges now facing major oil companies, BP recently took the decision to sell its entire Alaskan operations to another company, Hilcorp, including the lease to drill in the Refuge. This doesn’t mean that BP is now free from its responsibilities for its impacts in the Arctic or no longer accountable for whatever happens next. If BP was serious about wanting to tackle climate change, it would be winding down its operations in Alaska, leaving the remaining oil in the ground and making sure that the lease is never acted upon. Instead, it has guaranteed that every last drop in Prudhoe Bay will be extracted – there are estimated to be another billion barrels there – and that the Refuge will continue to be a target for oil exploration.

The British Museum’s hypocrisy here is breathtaking. It continues to partner with and promote one of the oil companies with the longest and most shameful histories of exploitation and pollution in the Arctic, while mounting an exhibition calling for the Arctic to be protected.

4. Citi: funding climate change and trampling Indigenous rights

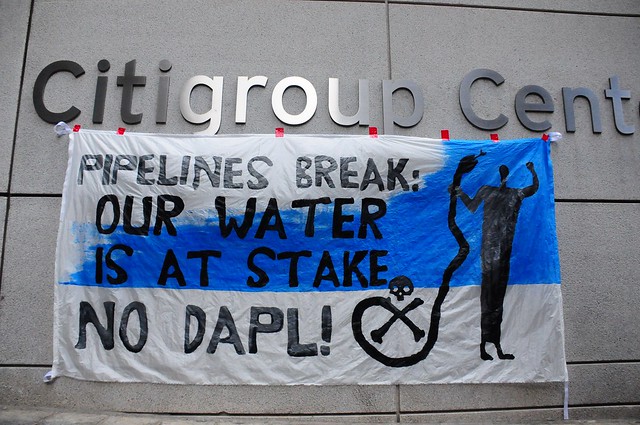

The British Museum has decided that US bank Citi should be the title sponsor of the Arctic exhibition – officially it is known as “The Citi Exhibition”. Citi’s branding comes into direct conflict with the exhibition’s core focus on the impacts of climate change on Indigenous Arctic peoples and their culture. Citi was recently named as the world’s third biggest funder of fossil fuels in the four years since the Paris Agreement was adopted, and has been backing Arctic drilling projects for decades.

In response to a powerful campaign led by Indigenous people, the bank pledged in April to stop directly funding Arctic drilling projects. However, Citi is still funding many of the biggest oil companies and so will almost certainly be providing financial backing to some of those firms gearing up to bid for new leases to explore and drill in the Arctic Refuge.

Citi also provided more finance to BP than any other bank last year. Despite its undeniable commitment to continuing fossil fuel extraction – including backing many projects facing Indigenous-led opposition such as the Keystone XL tar sands pipeline, the Dakota Access Pipeline and crude oil extraction in the Amazon – Citi is using its sponsorship of the exhibition to claim it has a strong stance on Indigenous rights and climate change. The reality of Citi’s investments in the fossil fuel industry are easy to research and yet, with shocking hypocrisy, the British Museum approved the following quote for the exhibition’s press release:

James Bardrick, Citi Country Officer, United Kingdom says:

“As a global bank, we play an essential role in financing a sustainable economy and supporting indigenous peoples’ rights. We are particularly proud to partner with the British Museum for the forthcoming Arctic: culture and climate exhibition that sheds light on the formidable artistic expression and ecological knowledge of the Arctic populations. We are committed to financing and facilitating clean energy, infrastructure and technology projects that support environmental solutions and reduce the impacts of climate change, on rich and diverse communities such as those that inhabit the circumpolar Arctic.”

5. FAQs

BP isn’t sponsoring this exhibition – so why are you raising the issue of its partnership with the museum?

BP has been a prominent sponsor of the British Museum for over 26 years and, over that time, the oil giant has had the opportunity to boost its brand as well as use the museum’s iconic building for networking events and its Annual Business Reception. The company’s name is also engraved in the marble wall of the central Reading Room and the museum’s main lecture theatre is named “The BP Lecture Theatre”. Both the Director and Chairman have enthusiastically defended the museum’s partnership with BP. While BP’s logo might only appear on specific exhibitions, the benefits it receives are ongoing and its relationship is deeply entrenched.

Crucially, BP was the biggest operator in the Alaskan Arctic for 60 years, producing over 13 billion barrels of oil. It was a massive emitter of greenhouse gas emissions which has contributed to the rapid changes in climate we are witnessing today. Despite recently announcing an “ambition” to become net zero by 2050, recent reports have shown that BP’s climate credentials are hugely overstated and the company is still not on a path that is compatible with preventing dangerous climate change.

There is a clear ethical conflict in hosting an exhibition that directly addresses the impacts of climate change while continuing to give legitimacy to a company that has historically produced vast amounts of greenhouse gas emissions and also continues to invest billions in the production of new fossil fuels.

Surely it’s a good thing that the British Museum is hosting an exhibition on climate change?

We welcome the museum’s decision to host an exhibition on the Arctic, curated and developed in close collaboration with Indigenous artists and communities. Too often, Indigenous peoples’ voices and perspectives are sidelined in discussions about how we respond to climate change and this exhibition is providing a rare and important platform for their perspectives to be heard.

Museums are not neutral spaces though. Who the museum accepts money from – not just the exhibitions and events it decides to host – reflect its underlying values. In this case, the museum is saying one thing about climate change while doing another. It is possible to praise the strengths of the exhibition itself but also call on the museum to be ethically consistent and end its relationship with BP.

How do the Indigenous artists and contributors whose work is displayed in the exhibition feel about your campaign?

Our protest on the 21st October 2020 is an act of solidarity with those Indigenous groups that are resisting oil extraction in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. It joins the dots between Citi and BP’s past involvement and investment in Arctic drilling and those companies and banks that are pursuing new leases today.

We recognise and appreciate that there are many Indigenous groups and communities in the Arctic who will have contrasting views about these issues. Our hope is that our protest opens up a space for a wider conversation between the museum, Indigenous artists and communities involved in the exhibition, and other stakeholders.

Haven’t BP gone green now and committed to reduce its emissions in line with the Paris Agreement? Surely that makes it ok for the museum to partner with the company?

Absolutely not. New BP CEO Bernard Looney announced back in February a new “Net Zero by 2050” ambition which in some ways does go further than other oil majors – but that’s not saying a lot. On closer examination, in turns out there are many loopholes that have caused us to question whether the firm’s announcement really is such a significant shift. Like other oil companies, BP has only set “an ambition” – not a binding target – so it still has wriggle room to go “back to petroleum” just as it has in the past.

Oil Change International‘s recent analysis showed that BP is still not aligned with the Paris goals and shone a spotlight on how the company’s headline aim of “cutting production by 40%” actually excludes “around 30 percent of the carbon pollution associated with its extraction investments.” A subsequent report by Transition Pathway Initiative has also concluded that BP’s business plans do not align with the Paris goals. Specifically, it pointed out that the company’s new emissions targets for its operations and production covered products made using its own and third-party crude. However, they do not cover those products BP trades, which made up more than half of everything it sold last year.

BP’s new plans still involve exploring for new sources of oil and gas we can’t afford to burn, and extracting fossil fuels in 2050, when we need to have transitioned away from them completely. It plans to achieve ‘net zero’ by offsetting these emissions using unproven, uneconomical technology such as carbon capture, utilisation and storage (CCUS). As such, BP is still definitely a driver of climate change, and until it has a firm commitment to rapidly phase out fossil fuel production at the pace required to meet a target of 1.5C, it will continue to be firmly part of the problem.

Doesn’t the British Museum need to take money from BP and Citi given the impact of Covid-19 on its finances?

The financial pressures facing museums and the wider cultural sector due to Covid-19 are unprecedented. We also recognise that it has been front-of-house workers and those from under-represented groups that are the ones who have been most impacted by the pandemic, and put at risk of redundancy and unsafe working conditions, while those in well-paid positions have often retained their salaries.

In the past few years, the tide has turned and very few cultural institutions now accept funding from fossil fuel companies. Calling on the British Museum to end its relationship with BP is simply asking the museum to come into line with the wider sector. While the British Museum does face financial pressures, its stature and scale means that it is able to tap into a wide range of funding sources, unlike smaller regional museums and arts organisations.

The case against BP’s partnership with the British Museum is clear cut. With regards to Citi, the British Museum must now review its due diligence and consider whether it can continue to partner with the bank while it remains the world’s third largest investor in fossil fuels. Those companies that are not genuinely committed to phasing out fossil fuels in line with the Paris Climate Accord should have no place promoting themselves within our cultural institutions, and the British Museum should not be giving Citi a platform to gloss over its fossil fuel investments and trumpet its record on Indigenous rights which is widely contested.

While the government recently announced a package of support for the cultural sector, it did not go far enough. Many workers have needlessly been made redundant and many cultural organisations are struggling to survive. The cultural sector has long been a net contributor to the UK economy. The government should provide full and comprehensive support that both safeguards jobs and allows the sector to thrive again in the future.